Ming M. Boyer, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-106549-4, PDF

There are increasing calls to center social groups or group identities in the study of political communication (e.g., Kreiss et al., 2024; Lane & Coles, 2024). To date, most work examines social groups as represented in and exposed to political communication. In contrast, little attention has been paid to how these groups create political communication themselves. However, increasingly politicians and citizens actively contribute to the political information environment, for example through direct communication on social media (Newman et al., 2024)—which are an important ground for social activism and identity politics (Jost et al., 2018). As group identities are salient when they are explicitly discussed (Turner et al., 1987), the identity of the communicator likely affects what and how they communicate about politics (Giles, 2012; Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Therefore, how communicators’ group identities affect their messaging is an essential factor in contemporary political information environments.

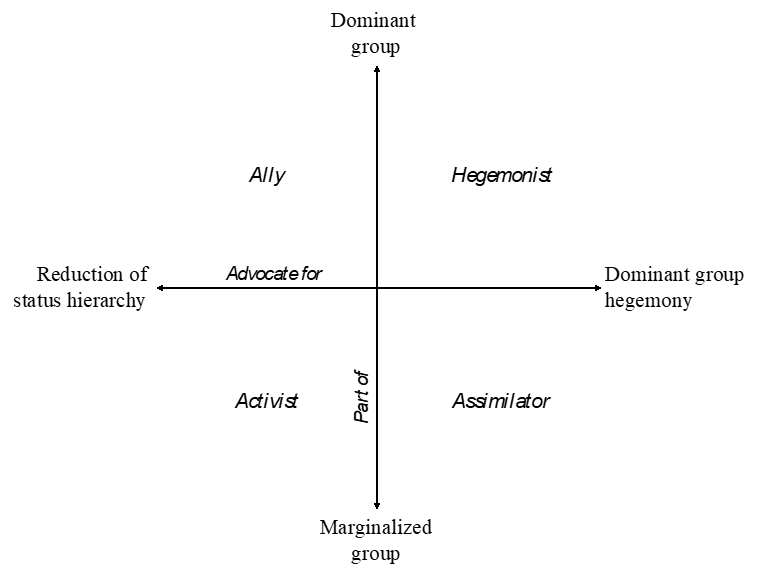

In this brief article, I make a case for the study of social groups as active communicators, i.e., investigating how different groups communicate about (identity) politics. I label this political group communication. In order to promote its systematic investigation, I propose a framework that distinguishes between the group that one is part of and the group that they advocate for. This leads to four archetypal communicators in political group communication (Activist, Ally, Hegemonist, and Assimilator) that may guide the study of group members’ communication patterns, the perceptions of communicators, and the effects of their communication. This way, I aim to kickstart a systematic investigation of how social groups actively shape the political information environment.

Why Study Political Group Communication?

Political communication research has been slow to embrace group identity in its theories, research aims, and methodologies (Kreiss et al., 2024; Lane & Coles, 2024; McGregor et al., 2025; Ramasubramanian & Banjo, 2020). Identity-centering scholarship is obstructed by narrow methodological views on social science that excludes fields that study identity most thoroughly (McGregor et al., 2025) and the focus on Europe and the United States has narrowed the scope of what should be studied (Ramasubramanian & Banjo, 2020). However, the circumstances in these regions have changed dramatically over the last two decades. The far right has gained political ground, creating a context of overt denial of equal rights and threats to marginalized groups (Knüpfer et al., 2024; Noury & Roland, 2020). Perhaps in response, attention to identity in the field of political communication is growing (Kreiss et al., 2024).

The study of group identities in political communication can largely be divided into four lines of inquiry. First, work into media representation shows that marginalized groups are under- and misrepresented in journalistic media (e.g., Eide, 2011; Jamil & Retis, 2023; Poindexter et al., 2003). Second, research into groups’ media selection indicates that citizens gravitate toward news that bolsters their identities and avoid news that threatens them (e.g., Abrams & Giles, 2007; Appiah et al., 2013; Hiaeshutter-Rice et al., 2024). Third, research investigates how groups process political information when they are exposed to it. Similar to media selection, this shows that citizens tend to interpret information to strengthen positive group-based self-perceptions, and avoid negative ones (e.g., Boyer et al., 2022; Han & Federico, 2018; Kahan et al., 2007). Finally, studies examining the effects of political information about groups show that negative portrayals of minorities can cause harmful attitudes among the majority and self-exclusion among minority members (e.g., Lajevardi, 2021; Mastro & Kopacz, 2006; Ramasubramanian, 2010). This includes work that focuses on the way identities are affected by media (e.g., Boyer & Lecheler, 2022; Saleem et al., 2019).

While these lines of enquiry have led to crucial insights, they all study groups as objects of coverage and/or as consumers of political information. Social groups are represented in and exposed to political communication. We thus largely miss a systematic investigation of groups as active communicators about politics. In other words, there is a need for theory and knowledge about political group communication—what emotions, arguments, identity markers, or other aspects of communication members of different groups use when they (re)negotiate their positions in society through political communication.

Studying political group communication is imperative due to two major developments in the political information environment. First, political actors increasingly advocate overtly for or against subgroups of the population with a distinct group identity – they practice identity politics (Fukuyama, 2018; Klandermans, 2014; Noury & Roland, 2020). This means that political arguments are increasingly defined by differences in, for instance, nationality, race/ethnicity, geography, religion, ability, gender, or sexuality—forming a political cleavage between those who focus on universality and those who focus on the rights of particular social groups (Westheuser & Zollinger, 2024). In short, social groups and group identities have become more important in political communication. Therefore, understanding them is essential to understanding the political information environment.

At the same time, public debate is shifting from legacy to social media (Newman et al., 2024)—and thus from journalistically edited content to direct communication. The transition from legacy to social media platforms has led to important shifts in the ways messages are communicated and rewarded in terms of engagement. For one, social media facilitate social identification in protest movements (Jost et al., 2018), causing identity-related political content to thrive. Moreover, as group identities are salient when they are explicitly discussed (Turner et al., 1987), content creators’ relevant social identities are likely salient when they create identity political communication. This means that intergroup behavior is dominant in online communication about social groups or identity politics (Giles, 2012; Tajfel & Turner, 1986; Turner et al., 1987). Hence, the group identities of citizens creating such content should contribute to what they say and how they say it.

In sum, as overt identity politics and direct political communication increasingly determine the political information environment, it is essential to study how social groups communicate about politics—i.e., to study political group communication.

Roles in Identity Politics

In order to effectively study political group communication, one must consider group identity at two levels (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). First, feeling part of a group usually defines group membership in social psychology (idem). For instance, most readers of this article will feel part of a gender group, as gender is a particularly strongly socialized group identity (Burns & Kinder, 2012). Such self-identification with a group most likely guides group communication (Tajfel & Turner, 1986), especially in situations in which this group is particularly salient (Turner et al., 1987)—such as when someone is actively communicating about it. Second, dominant and marginalized groups denote a structural hierarchy in society (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). Within gender, men are a dominant group compared to women. Women are perceived as less competent (cultural marginalization; Ellemers, 2018), are paid less for the same job (economic marginalization; idem), and are underrepresented in parliaments (political marginalization; Wängnerud, 2009). In an identity political discussion, one can thus be part of a relatively dominant or marginalized group.

Marginalized groups would benefit from an increased relative social status. However, to achieve this, dominant groups would have to give up some of theirs (Tajfel & Turner, 1986). From this perspective, it is thus often possible to distinguish between two sides of a debate—one that advocates for the marginalized group through a decrease in social hierarchy and one that argues for the sustained or strengthened hegemony of the dominant group. It follows that anyone taking part in such a debate can be part of the dominant or marginalized group, and they can advocate for one of them. While this simplification ignores the intersectionality of multiple identities that creates unique issues for subgroups that experience intersecting marginalization (Crenshaw, 1989), group interests are often experienced and structured in society as oppositional on a single dimension (Lowery et al., 2006). The #BlackLivesMatters movement, for example, silenced the issues of Black women by focusing only on race (Carney, 2016). While it is crucial to investigate how group experiences differ between intersectional groups and types of marginalization, which may affect their communication patterns, the structure of public debate determines individuals’ roles in identity politics, often defined by one dimension of identity.

Considering that individuals taking part in an (identity) political debate are (a) part of a social group in relation to the debate, and (b) argue in favor of a social group in relation to the debate, I propose to study political group communication through the four archetypal roles in Figure 1. I call dominant group members that advocate for ingroup hegemony ‘Hegemonists’ and marginalized group members that attempt to reduce the status hierarchy ‘Activists’. Following a plethora of earlier work (e.g., Droogendyk et al., 2016; Wiley & Dunne, 2019), dominant group members advocating for a reduction of status hierarchy are called ‘Allies’. In contrast, assimilating to the status hierarchy, marginalized group members advocating for dominant group hegemony are called ‘Assimilators’.

Figure 1. Archetypal roles in identity politics.

This framework may be utilized to study at least three aspects of political group communication. For one, it may address what communication looks like for each archetypal role. For example, arguments favoring the ingroup are consumed more often (Appiah et al., 2013; Knobloch-Westerwick & Hastall, 2010) and are better remembered (Schaller, 1992), especially when a group is specifically primed (Rule et al., 2010). As such, group members might have a preference to use arguments that include their group. For instance, natives may argue in favor of immigration because it is good for the economy—thus also for natives. Second, this framework may guide investigations of how communicators are perceived. For instance, allies’ political group communication can be perceived as performative (Olbermann & Reis, 2024) or selfish (Marshburn et al., 2021), suggesting the importance of perceived communicator authenticity. Third, the framework could help understand how messages affect receivers as communicated by each archetypal role. This may depend on a common relevant group identity between the sender and receiver (Mackie et al., 1990; Wilder, 1990), on the abovementioned perceptions about the communicator, and on individual attitudes and cross-pressures of other identities such as partisanship (Boyer et al., 2022). Particularly, the interaction between the message and the communicator’s identity may be of specific interest to maximize message effectiveness.

Conclusion

The discussion above illustrates how the four archetypal ‘roles’ presented in this paper may guide the investigation of three aspects of political group communication: the type of communication itself, perceptions of the communicators, and effects on audiences. This focus on group identity offers a fresh perspective, complementing the ubiquity of partisanship in political communication research (Hiaeshutter-Rice et al., 2024). As such, it is my hope that future studies will adopt this framework to investigate active political communication by social groups.

However, the current political situation requires responsible scholars to consider the risks involved in this kind of research. Specifically, in a context of increasing illiberalism and far-right threats to marginalized groups (Knüpfer et al., 2024), it is important that research supports the inherently democratic norm of equality between social groups—such as those based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, or ability—rather than the forces that undermine it. Therefore, scholars using this framework should carefully examine for which purposes the generated knowledge can be used or abused. The first, descriptive, line of research—illuminating differences between the roles in terms of their emotions, arguments, and other aspects of communication—can be explored with relatively little concern. The findings may help expose tendencies and strategies on both sides that may be used to more effectively increase equality in contemporary democracies and undermine attempts to the opposite. However, the second and third avenues for research—the exploration of perceptions of communicators of different groups and of the persuasive effects of political group communication—should be treated more carefully in order to avoid designing a playbook for antidemocratic forces. In this way, researchers can assure that the use of this framework may help create a world with more equality, a world with more democracy.

References

Abrams, J. R., & Giles, H. (2007). Ethnic identity gratifications selection and avoidance by African Americans: A group vitality and social identity gratifications perspective. Media Psychology, 9(1), 115–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260709336805

Appiah, O., Knobloch-Westerwick, S., & Alter, S. (2013). Ingroup favoritism and outgroup derogation: Effects of news valence, character race, and recipient race on selective news reading. Journal of Communication, 63(3), 517–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12032

Boyer, M. M., Aaldering, L., & Lecheler, S. (2022). Motivated Reasoning in Identity Politics: Group Status as a Moderator of Political Motivations. Political Studies, 70(2), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321720964667

Boyer, M. M., & Lecheler, S. (2022). Social mobility or social change? How different groups react to identity-related news. European Journal of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1177/02673231221105168

Burns, N., & Kinder, D. (2012). Categorical politics: Gender, race, and public opinion. In A. J. Berinsky (Ed.), New Directions in Public Opinion (pp. 139–167). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfs042

Carney, N. (2016). All Lives Matter, but so Does Race. Humanity & Society, 40(2), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0160597616643868

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139–167. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

Droogendyk, L., Wright, S. C., Lubensky, M., & Louis, W. R. (2016). Acting in Solidarity: Cross‐Group Contact between Disadvantaged Group Members and Advantaged Group Allies. Journal of Social Issues, 72(2), 315–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12168

Eide, E. (2011). Down There and Up Here: Orientalism and Othering in Feature Stories. Hamptons Press.

Ellemers, N. (2018). Gender Stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1), 275–298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719

Fukuyama, F. (2018). Against identity politics: The new tribalism and the crisis of democracy. Foreign Affairs, 97(5), 90–114.

Giles, H. (2012). Principles of Intergroup Communication. In H. Giles (Ed.), The Handbook of Intergroup Communication (pp. 3–16). Routledge.

Han, J., & Federico, C. M. (2018). The polarizing effect of news framing: Comparing the mediating roles of motivated reasoning, self-stereotyping, and intergroup animus. Journal of Communication, 68(4), 685–711. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy025

Hiaeshutter-Rice, D., Madrigal, G., Ploger, G., Carr, S., Carbone, M., Battocchio, A. F., & Soroka, S. (2024). Identity Driven Information Ecosystems. Communication Theory, 34(2), 82–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtae006

Jamil, S., & Retis, J. (2023). Media Discourses and Representation of Marginalized Communities in Multicultural Societies. Journalism Practice, 17(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2022.2142839

Jost, J. T., Barberá, P., Bonneau, R., Langer, M., Metzger, M., Nagler, J., Sterling, J., & Tucker, J. A. (2018). How Social Media Facilitates Political Protest: Information, Motivation, and Social Networks. Political Psychology, 39(S1), 85–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12478

Kahan, D. M., Braman, D., Gastil, J., Slovic, P., & Mertz, C. K. (2007). Culture and identity-protective cognition: Explaining the white-male effect in risk perception. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 4(3), 465–505. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849776677

Klandermans, P. G. (2014). Identity Politics and Politicized Identities: Identity Processes and the Dynamics of Protest. Political Psychology, 35(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12167

Knobloch-Westerwick, S., & Hastall, M. R. (2010). Please your self: Social identity effects on selective exposure to news about in- and out-groups. Journal of Communication, 60(3), 515–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01495.x

Knüpfer, C., Jackson, S. J., & Kreiss, D. (2024). Political Communication Research is Unprepared for the Far Right. Political Communication, 41(6), 1009–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2024.2414268

Kreiss, D., Lawrence, R. G., & McGregor, S. C. (2024). Trump Goes to Tulsa on Juneteenth: Placing the Study of Identity, Social Groups, and Power at the Center of Political Communication Research. Political Communication, 41(5), 845–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2024.2343757

Lajevardi, N. (2021). The Media Matters: Muslim American Portrayals and the Effects on Mass Attitudes. The Journal of Politics, 83(3), 1060–1079. https://doi.org/10.1086/711300

Lane, D. S., & Coles, S. M. (2024). P Stands for Politics, But What Does Politics Stand For? Locating “The Political” in Political Communication. Political Communication Report, 30.

Lowery, B. S., Unzueta, M. M., Knowles, E. D., & Goff, P. A. (2006). Concern for the in-group and opposition to affirmative action. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(6), 961–974. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.961

Mackie, D. M., Worth, L. T., & Asuncion, A. G. (1990). Processing of Persuasive In-Group Messages. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 19« (Vol. 58, Issue 5).

Marshburn, C. K., Folberg, A. M., Crittle, C., & Maddox, K. B. (2021). Racial bias confrontation in the United States: What (if anything) has changed in the COVID-19 era, and where do we go from here? Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220981417

Mastro, D. E., & Kopacz, M. A. (2006). Media representations of race, prototypicality, and policy reasoning: An application of self-categorization theory. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 50(2), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem5002_8

McGregor, S. C., Coe, K., Saldaña, M., Griffin, R. A., Chavez-Yenter, D., Huff, M., McDonald, A., Redd Smith, T., White, K. C., Valenzuela, S., & Riles, J. M. (2025). Dialogue on difference: Identity and political communication. Communication Monographs, 92(2), 217–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2025.2459648

Newman, N., Fletcher, R., Robertson, C. T., Ross Arguedas, A., & Nielsen, R. K. (2024). Reuters Institute digital news report 2024.

Noury, A., & Roland, G. (2020). Identity Politics and Populism in Europe. Annual Review of Political Science, 23, 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-033542

Olbermann, Z., & Reis, M. (2024). It’s a Match: The Impact of Influencer-Message Congruence and Recipients Identity on Perceptions of Rainbowwashing. Journal of Promotion Management, 31(1), 39–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2024.2422877

Poindexter, P. M., Smith, L., & Heider, D. (2003). Race and Ethnicity in local Television News: Framing, Story Assignments, and Source Selections. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 47(4), 524–536. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4704_3

Ramasubramanian, S. (2010). Television Viewing, Racial Attitudes, and Policy Preferences: Exploring the Role of Social Identity and Intergroup Emotions in Influencing Support for Affirmative Action. Communication Monographs, 77(1), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903514300

Ramasubramanian, S., & Banjo, O. O. (2020). Critical Media Effects Framework: Bridging Critical Cultural Communication and Media Effects through Power, Intersectionality, Context, and Agency. Journal of Communication, 70(3), 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqaa014

Rule, N. O., Garrett, J. V., & Ambady, N. (2010). Places and faces: Geographic environment influences the ingroup memory advantage. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(3), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018589

Saleem, M., Wojcieszak, M. E., Hawkins, I., Li, M., & Ramasubramanian, S. (2019). Social identity threats: How media and discrimination affect Muslim Americans’ identification as Americans and trust in the U.S. Government. Journal of Communication, 69(2), 214–236. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz001

Schaller, M. (1992). In-group favoritism and statistical reasoning in social inference: Implications for formation and maintenance of group stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.1.61

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson Hall.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the Social group: A Self-categorization Theory. Blackwell.

Wängnerud, L. (2009). Women in Parliaments: Descriptive and Substantive Representation. Annual Review of Political Science, 12(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.053106.123839

Westheuser, L., & Zollinger, D. (2024). Cleavage theory meets Bourdieu: studying the role of group identities in cleavage formation. European Political Science Review, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773924000249

Wilder, D. A. (1990). Some Determinants of the Persuasive Power of In-Groups and Out-Groups: Organization of Information and Attribution of Independence. In Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (Vol. 59, Issue 6).

Wiley, S., & Dunne, C. (2019). Comrades in the Struggle? Feminist Women Prefer Male Allies Who Offer Autonomy- not Dependency-Oriented Help. Sex Roles, 80(11–12), 656–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0970-0

Author

Ming M. Boyer is a research associate in Communication Science at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, focused on group identity in political communication and negativity in politics and media. Currently, he holds a NWO Veni grant on political group communication, combining manual and automated content analyses with experimental research. Dr. Boyer has published in leading journals such as Political Communication, Journal of Communication, and the European Journal of Political Research. He currently serves on the editorial board of Human Communication Research.