Platforms, Power, and Politics: A Model for an Ever-changing Field

Ulrike Klinger, European University Viadrina

Daniel Kreiss, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Bruce Mutsvairo, Utrecht University

http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/refubium-39045; PDF

In the past six months alone, many of the preconditions for political communication have changed, creating new challenges and research opportunities for scholars. Elon Musk’s Twitter takeover was a powerful reminder that we should not trust platforms with all our data, rely on them as spaces for public discourse, or otherwise believe they will serve as digital services for eternity. Critics have bemoaned the smashed china at Twitter, as an unrestrained billionaire owner changed key affordances and policies of the platform, fired most of the workforce, and undermined the company’s revenue streams. As scholars, we’ve lost access to Twitter’s data API (application programming interface), and for the foreseeable future, studying Twitter will require significant workarounds.

Roughly at the same time, the world has realized the impressive development of generative AI, experimenting with technologies like ChatGPT and Midjourney. As with all new technologies, there is both fascination and fear regarding the impact of AI on political communication (among many other things). Being the early adopters they are, political actors from far-right parties have already begun to post AI-generated images on social media, claiming that AI helped them to illustrate feelings and perceptions for which no photographs exist (Lauer 2023). As platforms and their technologies evolve, they will continue to shape opportunities and incentives for some political actors and movements, including ones that threaten democratic systems. If one were inclined towards pessimism, it would be easy to worry about the future of a shared reality and the foundations of democratic discourse.

However, we can also understand the recent developments as anything but new. They illustrate what social science has known and discussed for decades, including prominent thinkers such as Joseph Weizenbaum or Herbert Marcuse, and those in our own era, such as Ruha Benjamin and Safiya Noble: Those who control key technologies have power in society. And those who use these technologies often lack information about how they work or how this power is exerted. In recent years, political communication researchers have discussed these things under the rubrics of algorithms and algorithmic accountability, network or social media logic, datafication, and surveillance capitalism, just to name a few. Platforms are not neutral tools – through their design, policies, monetization strategies, and attention-grabbing capabilities they incentivize and amplify certain forms of political speech and dramatically lower the costs of some types of communication. The events at Twitter and the emergence of generative AI for everyday purposes are prescient reminders that key questions of our time center on who wields power through and over technologies.

Our model for an increasingly transforming field

Given these rapid changes, we need new conceptual approaches to understanding how political communication is shaped by and shapes, platforms. This seems especially important in light of the exciting methodological advances in the field over the previous decade. In our forthcoming book, designed to be an accessible introduction to the field (Klinger, Kreiss & Mutsvairo 2023), we propose a new model for understanding how politics, power, and platforms relate to each other. We also advocate for the growing field to include techno-political developments from regions of the world that are often underrepresented in our collective scholarship. It is imperative that political communication scholars understand platform power as it shapes political and social contexts, even as platforms, in turn, are themselves embedded in them. These contexts shape their governance and the political dynamics that play out on them.

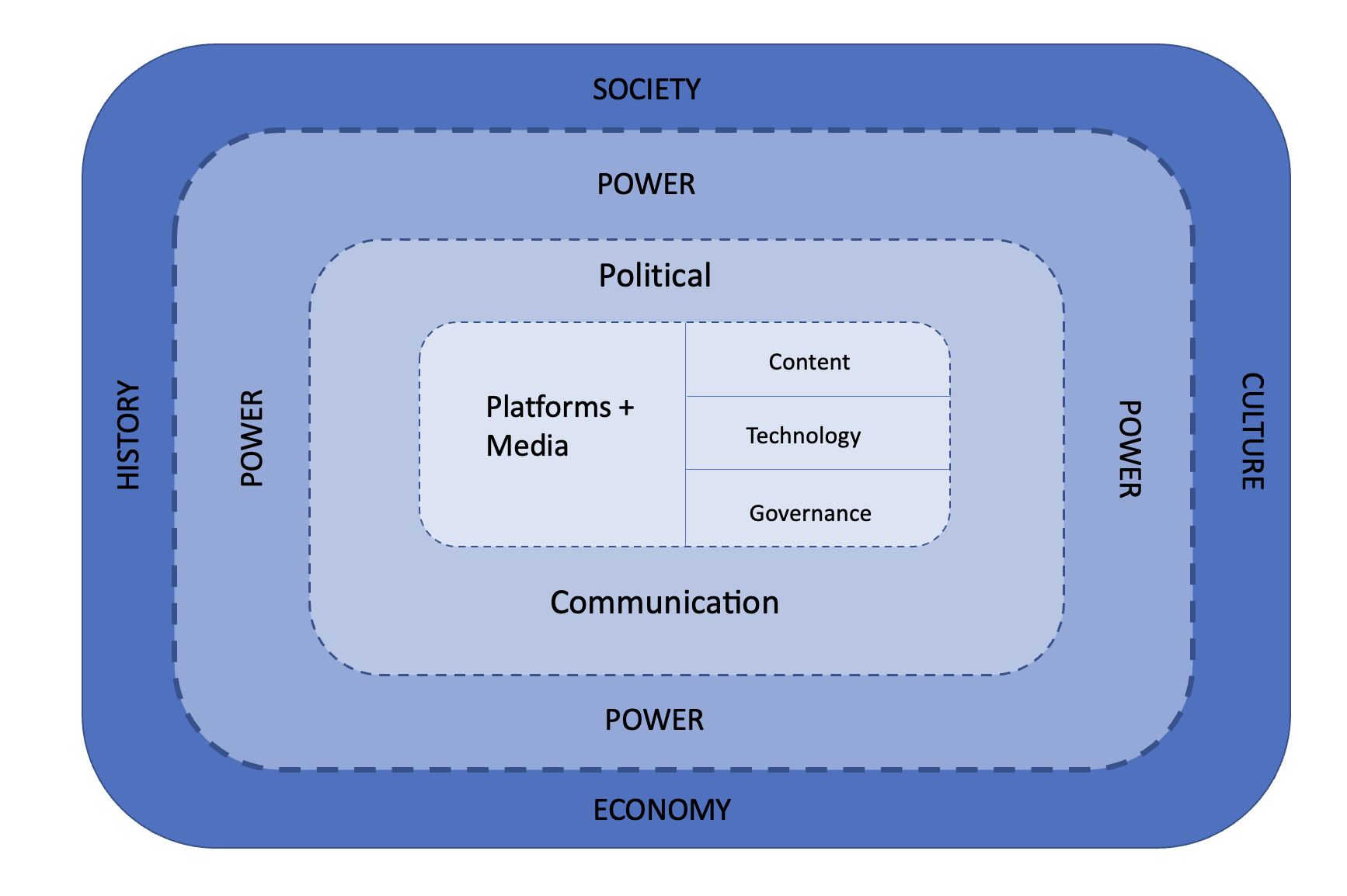

Figure 1: Reproduced from (Klinger, Kreiss & Mutsvairo 2023)

As we argue, platforms sit at the core of contemporary political communication, alongside other forms of media, and are arranged into systems. Increasingly, platforms are the primary way citizens encounter political information and engage with it, as well as communicate with others about things that concern their shared lives. Political content on platforms is created by political and media actors of all sorts, including journalists, activists, political strategists, elected officials, and citizens themselves. Platforms are not neutral distribution channels, however (e.g. Nielsen & Gantner 2022; Gillespie et al, 2020). Platform technologies, their affordances and algorithms, and their governance, through policies, regulations, business models, and the organizations behind them, shape the way political content is distributed and flows on and across platforms. In other words, platforms are not just code. To understand how political communication works on platforms, we need to look beyond the content found on them and also reflect on the technologies and governance mechanisms that shape how they work – in addition to the dynamics of the media systems they are embedded in.

Political communication depends highly on context – which is why even if platforms were the same everywhere (and they are not!), political communication would still be different. If we want to understand the impact of platforms on polities, including their role in political communication phenomena such as disinformation or populism, we must take into account the specific historical, social, cultural, and economic contexts they operate in, as well as the relations of power shaped by the structural forces that play out upon them. For instance, Facebook has been illegal in Uganda since 2021. The East African nation’s long-serving leader, Yoweri Museveni, took personal offense when the tech giant deleted hundreds of fictitious supporter accounts ahead of the Ugandan elections in 2021. In the meantime, Twitter took on an outsized role in the country’s politics. As this example shows, political contexts matter profoundly for the role platforms play in political communication, even as political actors themselves recognize that platforms exert power that affects political processes. Political, historical, social, and economic contexts shape the power platforms have and exercise while also shaping the very contexts that they and the social groups that contest power on them operate in. What makes our time unique is that platforms and the tech giants behind them have become extremely powerful and influential global actors, sometimes even more powerful than individual nation-states. Platforms not only track and trace users, they also determine who should use their services and how they can use them – such as the forms of political expression they can engage in, the affiliations they can have, and the political ends towards which they can work.

The dashed lines in our model capture how power runs in both directions. Power rooted in historical, social, cultural, and economic contexts shapes how political communication operates and the workings of platforms and media. For instance, many platforms are commercial and therefore operate in capitalistic economic contexts. Others are more directly shaped by the political systems they operate in, especially state-backed platforms such as TikTok. The historical experiences of nations influence how and even if media and platforms are regulated. As the Uganda example shows, platforms and media, however, have power, too. They do not command armies or shape class structures in society, but the content they differentially host, promote, and disseminate, the technologies they unleash unto society, and their internal governance decisions impact what citizens know (or do not know), what they share, how, and with whom, and how they form opinions, mobilize, or radicalize. Platforms (and media) shape which political actors, wielding which communication styles, gain visibility and attention in ways that affect the workings of political institutions such as parties, parliament, or senate. Thus, platforms and media are not just shaped by forms of social, political, cultural, or economic power. They themselves wield power over the societies, political systems, and media regimes they operate in. And, over time, platforms have proven they have got the power to shape who commands the army, undoubtedly showing how they have transformed political communication.

AI – a danger in upcoming elections?

So how does all this play out in political communication, and how does our model help conceptualize this? Let’s take a closer look at the AI tools that have recently come into prominence. Language models like ChatGPT or image-generating AI applications are technologies of content production, and their societal impact is closely connected to the distribution power of platforms and media. The artificially created image of “Balenciaga Pope” (Elias & Razik, 2023) for instance, could only stun people around the world the way it did when people actually see the image. It is precisely the link between the power of platforms and the endless possibilities for automatically creating texts and images to be distributed across these platforms that lies at the root of the moral panic and hype around AI in the past months. Together, AI technologies and the platforms that afford them reach and scale will influence political communication practices in upcoming elections and other political processes.

However, both platforms and AI do not exist in a vacuum. They are industry products shaped by the cultures, economies, societies, and histories of those who create and operate them. For example, the fact that Open AI, the company behind ChatGPT, has transformed from an open-source, non-profit organization into a highly commercial company controlled by Microsoft, profoundly impacts the technology, power, and economic structures behind it. Even as Microsoft is starting to embed ChatGPT technology into its products used by millions of people to communicate and obtain information, the training data for the automation remains opaque – which is why its potential biases are largely unknown. History, culture, and all sorts of social bias and discrimination are likely inscribed in this training data and thus in the automatically generated texts and images that systems like ChatGPT produce (e.g.: Raji et al., 2020).

When automatically created content is used in political communication, these technologies can run counter to existing institutions, political systems, media systems, party systems, and various forms of governance. Although it has taken Western democracies over a decade to find regulatory answers to many collateral effects of social media platforms (most notably in the European Union), platform governance can exert power over and shape technologies. For instance, Musk’s capricious changes at Twitter may cost the company hefty fines or even a ban in Europe if his company were to fail to put appropriate measures in place to fight disinformation as required by the EU’s Digital Services Act. Measures have been put in place to protect citizens’ digital safety and those who contravene the law face significant fines or temporary suspensions. What’s more, if enacted, the proposed and hotly debated Artificial Intelligence Act will have far-reaching implications for the use and governance of artificial intelligence across Europe. The (currently drafted) provisions of the AI Act apply to technologies used by people in Europe, irrespective of their local origin, and they apply to large generative AI models like ChatGPT and Midjourney. Due to such models’ general purpose, they will qualify as high-risk systems under this new regulation (Hacker et al. 2023). In addition, there are many provisions governing AI on subnational levels in Europe (Liebig et al, 2022). This means that regulation is already underway in some regions to mediate the potential direct and collateral effects of such tools on democratic societies and political communication.

So, on the one hand, we might fear that the combination of generative AI and the dismantling of content moderation at Twitter could wreak havoc in upcoming elections. In 2024, both the European Parliament and the US presidential elections will take place. In addition, in a worst-case scenario, political communication scholars will be extremely limited by data access restrictions in their attempts to study these campaigns on platforms. On the other hand, our model helps us understand how it is not technologies alone that damage or inflict harm on democratic processes but how political actors choose to use them and the institutional guardrails that guide their behavior along with the workings of platforms and transformative technologies. The relationship between platforms, power, and politics runs both ways, and thus the impact of technology on political communication is not the same everywhere but embedded in specific historical, cultural, social, and cultural contexts.

References

Elias M & Razik N. (2023). Balenciaga Pope’ might not have been real. But its impact is. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/the-feed/article/balenciaga-pope-might-not-have-been-real-but-its-impact-is/61v1i9h3x

Hacker, P. (2023). Understanding and regulating ChatGPT, and other large generative AI models. Verfassungsblog: On Matters Constitutional. https://verfassungsblog.de/chatgpt/

Gillespie, T., Aufderheide, P., Carmi, E., Gerrard, Y., Gorwa, R., Matamoros-Fernández, A. & West, S. M. (2020). Expanding the debate about content moderation: Scholarly research agendas for the coming policy debates, Internet Policy Review 9(4): 1-30.

Lauer, S. (2023). Wie gehen AfD & Co mit künstlicher Intelligenz um? https://www.belltower.news/ki-rechtsaussen-wie-gehen-afd-co-mit-kuenstlicher-intelligenz-um-148183/

Liebig, L., Güttel, L., Jobin, A., & Katzenbach, C. (2022). Subnational AI policy: shaping AI in a multi-level governance system. AI & SOCIETY, 1-14.

Klinger, U., Kreiss, D., & Mutsvairo, B. (2023). Platforms, Power, and Politics. An Introduction to Political Communication in the Digital Age. Cambridge: Polity (forthcoming, September 2023)

Nielsen, R. K. & Ganter, S. A. (2022). The Power of Platforms: Shaping Media and Society. Oxford University Press.

Raji, I. D., Smart, A., White, R. N., Mitchell, M., Gebru, T., Hutchinson, B., & Barnes, P. (2020, January). Closing the AI accountability gap: Defining an end-to-end framework for internal algorithmic auditing. In Proceedings of the 2020 conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency (pp. 33-44).

Ulrike Klinger is Professor of Digital Democracy at the European University Viadrina and Associated Researcher at the Weizenbaum Institute for the Networked Society in Berlin.

Daniel Kreiss is the Edgar Thomas Cato Distinguished Professor in the Hussman School of Journalism and Media at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a principal researcher of the UNC Center for Information, Technology, and Public Life.

Bruce Mutsvairo is a Professor and Chair in Media, Politics and the Global South at Utrecht University.